I visited the People’s History Museum in Manchester yesterday which contained a collection of Trades Union Banners.

For hundreds of years, organisations that have a marching tradition have made banners in order to identify themselves. This includes trade unions, friendly societies, temperance groups, co-operative societies, Orange orders, suffrage, women's and peace organisations and political parties, but also non-political organisations like churches, chapels and Sunday schools. Political organisations that did not have a tradition of processions, like for instance the Anti Corn Law League or the anti-slavery movement, did not produce banners. Historians can 'read' banners for evidence in much the same way as documents.

The banners with which we are most familiar today are those of the mass trade union movement. The trade societies evolved into the skilled workers' New Model Unions of the 1850s onwards. These unions' banners retained many of the same elements, such as the tools and processes of the trade, of the earlier trade societies. The 1889 Great Dock Strike brought about a surge in union membership from unskilled workers and a great demand for banners.

The style in which I am photographing my workers is similar to the way workers are depicted on these banners – a sense of dignity, heroism and pride is captured.

Working people had created a rich subculture for themselves, dense with institutions, clubs, unions, education societies, cooperatives, chapels (Gorman, 1986:16)

From it the trade unions emerged and from it they drew their imagery: from old craft, Freemasonry, friendly society, temperance group, from the chapel and the Sunday school, from the bible and from Bunyan (Gorman, 1986:16)

After 1825 the unions rapidly abandoned the secret society (though not its insignia). They marched the streets with their banners (Gorman, 1986:16)

Already by 1831 the miners were beginning their career as the greatest banner bearers of them all: at Jarrow they paraded, each colliery with its own. (Gorman, 1986:16)

The banners were out in force at political rallies, the Ten Hours Campaign meetings; in 1834 the unions marched against the transportation of the Dorchester men like regiments of guards, strictly marshalled behind thirty-three banners in battle array (Gorman, 1986:16)

The earliest banner John Gorman has been able to find dates from the 1820s; it is in the 1840s that a recognisable tradition begins, that George Tutill who was to become banner-maker-in-chief to the unions sets to work (Gorman, 1986:16)

Over two generations of travail and turmoil, in the teeth of back-breaking and heart-breaking resistance, the working classes, against all odds, had established a presence (Gorman, 1986:16)

As their unions began to harden into some permanence and continuity, as unionism itself stiffened into a ‘tradition’, so their pageantry and symbolism began to firm and steady into a kind of permanence. (Gorman, 1986:16)

Their banners became enterprises of the spirit, large and silken and heavy and expensive; memorials to a certain permanence. (Gorman, 1986:16)

And the heraldry first blazoned in this slowly forming tradition was the heraldry of presence (Gorman, 1986:16)

Presence

During the 1840s union banners began to be made in the general style which remained in favour for a hundred years: lavishly illustrated on both sides of silk panels, highly ornamented and trimmed, up to 4.9 by 3.7 metres in size, to be paraded in public, stately and striking (Gorman, 1986:16)

This uniformity, which extended to designs as well as materials, was due largely to one man, George Tutill, who set up in the banner-making business in 1837 and over the next fifty years earned for his business a virtual commercial monopoly and a world-wide market (Gorman, 1986:16)

Tutill made banners for a wide range of societies, but his speciality was union work (Gorman, 1986:17)

The basic forms and modes of banner art were fixed in the pudding time of mid-Victorian prosperity to the satisfaction of the labour aristocrats who then staffed the unions; these forms proved equally congenial to successive generations of new unionists at least up to the First World War; such adjustments as were made responded to the general movement of popular public taste, for example in advertising styles of the 1920s. (Gorman, 1986:17)

Even when taste had altered drastically, union men in the inter-war years seem to have been very reluctant indeed to move out of what had then become a tradition (Gorman, 1986:17)

It is a striking testimony to the aptness and fitness of George Tutill’s designs (Gorman, 1986:17)

While banners by the hundred were produced all over the country it was the Tutill banners which moved into the mainstream of union heraldry. It was they who established the tradition (Gorman, 1986:17)

These themes were central: unity, brotherhood, mutuality, coupled with an assertion of the essentially moral and innocent character of the organisation (Gorman, 1986:18)

They were never servile – ‘We bide our time’ – but the stress was always on conciliation not conflict. (Gorman, 1986:18)

And when they chose to advertise their service as benefit societies (as they did with increasing emphasis) their banners were drenched in the biblical imagery of the Good Samaritan (Gorman, 1986:18)

Cathedral and Commonalty

In the 1890s something like a banner mania seized working people and not only in their unions (Gorman, 1986:20)

Banners went everywhere, to meetings, demonstrations, funerals, even picnincs; the country broke into a rash of £50 raffles (Gorman, 1986:20)

In the decade 1890-1900 the British people seem to have wantoned in colour (Gorman, 1986:20)

Under the first impact of the new unionism the world of banners visibly expanded (Gorman, 1986:21)

The banner was essentially an expression of local, of branch pride and in a few years of tumultuous growth there was a profusion of new ideas (Gorman, 1986:21)

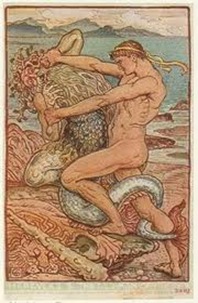

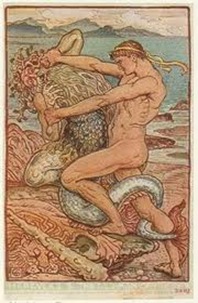

‘This is a Holy War’, proclaimed the militant export branch of the dockers, ‘and we shall not cease until all destitution, prostitution and exploitation is swept away’ and on their dramatic banner a hero wrestles a serpent amid solidarity slogans (Gorman, 1986:21)

‘Be sure you are right’, warns a lifebelt circling a ship, ‘then full speed ahead’ [see below] (Gorman, 1986:21)

The militancy of the ‘new unionism’ is vividly portrayed by a Herculean worker wrestling with the ‘serpent of capitalism’. The design derives from Walter Crane’s illustration of ‘Hercules and the Old Man of the Sea’, drawn for A Wonder Book, published in 1892. Tutill’s, who made the banner, frequently used Crane’s work as a ready reference for trade union banner designs. The banner would have been painted in the early 1890s and the forceful slogans represent a break with the conciliatory mottoes of the old craft unions. The reference to prostitution on the banner reflects the policy of the union which was formed during the Great Dock Strike of 1889 and aimed to change the wretched social conditions that prevailed in London’s dockland at the end of the last century. A recent discovery of some old glass negatives that escaped the bombing of George Tutill’s in 1940 show that the design was later copied, including the mottoes, for the New Monkton Main branch banner of the Yorkshire Minerworkers’ Association (Gorman, 1986:127)

Crane, Walter (1892) Hercules and the Old Man of the Sea. New York Public Library

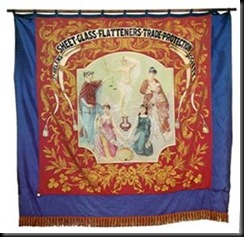

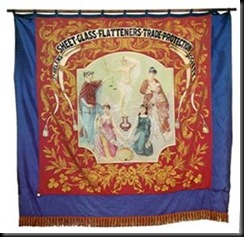

The banner of the Sheet Glass Flatteners, found in St Helens during the Pilkington troubles of 1970 and apparently unused since 1923, was strictly traditional, the parable of the bundle of sticks on one side and on the other a bevy of suitably symbolic ladies group around a flaccidly sexy Truth gazing into a mirror (Gorman, 1986:21)

| ![clip_image001[4] clip_image001[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhznUwmb1YQ6npD6lUSZnQDt7gBzLP2E6uob6gelXk8jjVHQl2a_F2wopso8b9SBjAn8JGXNxfB65zPC_CaaPPaQFvrsTQSkKINh69iYULBJlrdcIIVcZ_xd0lqK00K2wq24drXwin5z0Kk/?imgmax=800) |

This fine banner, painted in George Tutill’s studio, was found by strikers when they demonstrated at the offices of their own union, the National Union of General and Municipal Workers, during the Pilkington dispute at St Helens in 1970. The box in which the banner was found was lined with newspapers dated 1923 which may indicate the last time the banner was used. The Sheet Glass Flatteners were in existence in 1891 and the banner would seem to date from the last decade of the nineteenth century. The obverse of the banner illustrates the trade unionists’ popular fable about the power of unity: ‘A small child can break a single stick, but bound together a strong man cannot break them’ (Gorman, 1986:82)

The style of these banners is certainly cleaner and less cluttered; it is more accessible to modern taste, has less of the archaic and antique ‘charm’ of the earlier ones. (Gorman, 1986:21)

The difference is illusory. Banner art was no counterculture (Gorman, 1986:21)

Its duty was to communicate with the generality, it employed the media of the commons (Gorman, 1986:21)

It moved with public art, most notably with the poster and advertisement art of the 1920s (Gorman, 1986:21)

It was only when the living connection with working people was broken from the 1920s that banner art became a petrified subculture, a conscious archaism expressing ‘tradition’ and in due time a collector’s item worthy to rank, were it put practicable, with other fashionable Victoriana (Gorman, 1986:21)

From the 1900s the banners, particularly those of the miners marching in the vanguard of the labour movement, are a portrait gallery of leaders (Gorman, 1986:22)

Commonwealth

It was Walter Crane who shaped the first imagery of socialism among the unions (Gorman, 1986:22)

All these styles of Crane’s or derived from him appeared and reappeared in banner after banner before 1914, especially among the general unions (Gorman, 1986:22)

Sometimes there were effective variations. The Davenport branch of the Workers’ Union had a splendid scene in which a dazzling angel broke the chains of man’s slavery ‘Every bondsman has within himself the power to cancel his captivity’ (Gorman, 1986:22)

When slogans were used they were often spiky and personal, and the first pictorial socialism of the unions was in fact steeped in the modes and manners of a William Morris self-recreation in community. (Gorman, 1986:22)

[…] something of this tradition survived the war. Several banners follow the style, particularly among the general unions, with noble women, sometimes wrapped in streamers, leading sons of toil into commonwealth: ‘The World is my country, mankind my bretheren’. (Gorman, 1986:22)

The Lost Banners

At the May Day march in London in 1896 it was claimed that £20,000-worth of trade union banners were carried. (Gorman, 1986:27)

They were brilliant, silken sails of colour, up to 4.90 by 3.70 metres in size, painted with emblems and scenes showing the crafts and skills of the trade unionists who carried them (Gorman, 1986:27)

Some of the banners illustrated the hazards and dangers of the work in certain industries – a builder toppling from high scaffolding, a railway worker crushed between two trucks (Gorman, 1986:27)

Others painted a romantic vision of a better life to be gained by ‘Unity’ and ‘Reason not force’ (Gorman, 1986:27)

The peak period for banner carrying was undoubtedly the last decade of the nineteenth century when the enormous demand for banners from every sort of organisation, from Sunday schools to trade unions, amounted almost to a mania (Gorman, 1986:27)

Engravings, drawings, photographs and contemporary accounts confirm the vast numbers of ornate silk banners that would be paraded on every possible occasion during this time (Gorman, 1986:27)

In 1890 a newspaper reported 400 banners at a temperance society march in London! (Gorman, 1986:27)

The Banners Unfurled

Coats of arms or designs which appear to be armorial bearings on trade union banners derive from only two sources: the accredited arms of the craft guilds and the fertile imagination of the banner-painter or emblem-designer making free use of the heraldic art (Gorman, 1986:31)

In their efforts to acquire a ready-made history and strengthen their position in the eyes of the community, the bricklayers were not alone in looking backwards to the biblical forebears of their crafts, as if to imply a direct decendancy, an unbroken link from earliest times (Gorman, 1986:33)

While the bricklayers quoted Genesis, the shipwrights looked to Noah and the tinsmiths to Tubal Cain as the first worker in metals (Gorman, 1986:33)

The tailors […] claimed the making of the first suit of clothes for Adam and Eve, leaving the printers to appear as newcomers, tracing their origins to Gutenberg, Caxton and Alois Senefelder (Gorman, 1986:33)

It was left to the Carpenters to make the most audacious claim of all, depicting Joseph of Nazareth and declaring him ‘the most distinguished member of our craft on record’ (Gorman, 1986:33)

Whilst biblical antecendents and spurious coats of arms were contrived to bring immediate respectability, there is one instance of a savage parody of armorial bearings inscribed on a banner of 1833, during the agitation for the Ten Hours Bill (Gorman, 1986:33)

The trade unions without craft traditions looked to friendly societies, Masonic lodges and churches for the inspiration for the designs and mottoes for their banners (Gorman, 1986:33)

They and the craft unions also copied the rituals and regalia of such organisations, including oaths, initiation ceremonies, the regalia of office and structure of organisations (Gorman, 1986:33)

The earliest detailed account of the making of a trade union banner, that of the United Society of Weavers, describes the symbols that made up the total illustration, which included the ‘all-seeing eye of the Omnipotent King of Kings, looking down and diffusing the rays of glory on all beneath that never fail to light the path of the earnest worker and fearless spirit who believes in His love and almighty power’ (Gorman, 1986:33-34)

This ancient symbol, so widely used by Masons and friendly societies, is featured in hundreds of trade union banners up to the period of the First World War. (Gorman, 1986:34)

In 1834, in connection with their joining the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union, we have an account of the Nantwich shoemakers having a trade banner made, ‘emblematical of the trade’ painted by a ‘Herald painter, Thomas W Jones of Hospital Street […](Gorman, 1986:34-35)

It carried an illustration of St Crispin and the motto ‘May the manufactures of the sons of St Crispin be rod upon by all the world’ (Gorman, 1986:35)

Both the slogan and the patron saint were featured on banners of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives well into the twentieth century, a fine example being that of the Nos 1 and 2 branches, Northampton, made in the late 1920s and in regular use until 1962 (Gorman, 1986:35)

From the 1840s, the form and appearance of the banners was to remain basically the same, although the illustrations and slogans would alter of the years to meet the changes in society and trade unionism (Gorman, 1986:35)

Trade unionists turned quite naturally to the tools of the trade, place of work and thhe products of their labours as symbols of identity (Gorman, 1986:36)

Such banners had not only the advantage of ready recognition, but association of the union with its craft (Gorman, 1986:36)

They were also an honest reflection of the pride of the workers for their craft skills and their genuine concern for the quality and prosperity of the trade (Gorman, 1986:36)

The Hope of Labour

The banner was described as ‘a splendid addition to the colours of trade unionism’ (Gorman, 1986:40)

In their efforts to portray their trades, their purpose, their hopes and fears, the branches developed banner illustrations into an elaborate and telling popular art (Gorman, 1986:40)

One of the favourite forms of illustration during the 1890s was the picture parable, which showed with Sunday school simplicity the bad and good effects of two different course of action (Gorman, 1986:40)

The concept was not new and was widely used in Victorian times by every sort of ‘do good’ organisation (Gorman, 1986:40)

The employers used pictures to show that bad timekeeping led to the sack, while punctuality brought prosperity (Gorman, 1986:40)

The Banner Makers

As on the banner of the Witney branch of the Workers’ Union, David slaying Goliath might carry a militant trade union caption (Gorman, 1986:51)

All the popular emblems of truth, hope, justice, the ‘all seeing eye’ and every kind of medieval symbol Tutill could find were cleverly woven into composite designs and spurious coats of arms ready for any society requiring instant dignity and status (Gorman, 1986:51-52)

Another ready source of imagery for the Tutill business was the cartoons of Walter Crane (1845-1915). (Gorman, 1986:52)

Already famous as an illustrator and pre-Raphaelite artist when he was converted to socialism in 1884, Crane gave freely of his talents to the cause of labour to become the most influential of British artists in shaping the popular iconography of trade unionism (Gorman, 1986:52)

However, it was his cartoons, drawings made for socialist journals, Justice, Clarion, Commonweal and Labour Leader that were to become a standard reference for Tutill banners for forty years or more (Gorman, 1986:52)

Many more were inspired by his ‘Angel of Freedom’, derived from his original oil painting, Freedom, exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1885 (Gorman, 1986:52)

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhPjPh6Sn9nekUTFiAdX1jnw_AaS5eiIoVm6WlnHNyvhfeYuJBLc9fcrIBRFFR17myv4dl7zl6LT5VKKbXbIG7Yas9QMbegtV9u5YwnyDmgJdGbkiBN_yEmiBVfyGxOOzLDf3n9gX2brRKN/?imgmax=800)

Crane, Walter (1885) Freedom. Art Magick: Walter Crane (2010): http://www.artmagick.com/pictures/artist.aspx?artist=walter-crane

Described by Crane as a ‘vision breaking into the sunshine of spring’, the winged female figure was freely interpreted on the banners as a vision leading to the sunshine of socialism (Gorman, 1986:52)

![clip_image002[8] clip_image002[8]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhTWJg4vSDN9z0ySslcuWys7dfF2qim1HAWBb9HU1yQvFdx8AilEO3-hobId6AL0FwIUII7LbCJhNVwd_Ury4okLkB4jf_3vZDxsk9JjCf3YV-lu6lo1mIFcKiVeymbzLtyaBKzychElOc3/?imgmax=800)

The Chatham district banner of the Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers is based on an earlier design for a certificate of membership for the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners. In 1866 the executive committee commissioned a well-known artist of the time A J Waudby, to design both an emblem and a certificate. Fortunately the artist’s explanation of the original drawing is recorded. On one side of the banner (it is difficult to differentiate front and back when both are such fine paintings) is depicted Joseph of Nazareth, ‘the most distinguished member of the craft on record, being the reputed father of our Saviour’. Justice bearing the sword and the balance and Truth holding amirror are placed either side of him. The motto is ‘Credo sed caveo’ – ‘I believe but I beware’. The obverse shows an illustration representing ‘the centering of an arch adapted from a plate in Nicholson’s practical carpentry flanked with a carpenter and joiner’. Both figures are based on a portrait of James Blayne, chairman of the executive committee in 1862 and branch secretary of the Camden Town branch in 1866. Blayne stated in 1896, when applying for superannuation, that the saw shown in the hand of the carpenter on the left of the design was still in his possession. The banner, according to an old member of the union, G A Matthews, was made about 1899; a 5s levy was imposed on all members in the area to meet the cost. Mr Matthews recalls the banner being carried during local disputes and strikes before the First World War. Some time after 1927 the banner was returned to Tutill’s for reconditioning and alteration to the name and title. It was last carried through the streets of the Medway town on May Day, 1962. The banner is now part of the National Museum of Labour History collection. [now the People’s History Museum, Manchester]

Sources

- Gorman, John (1986) Banner Bright: An Illustrated History of Trade Union Banners, Essex: Scorpion Publishing Ltd

![clip_image001[13] clip_image001[13]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgy6TfiDhD1iOGVz8BwRvN8oKIVLcR9_hvpuIZ-yGbb0-jNLM31wg2WYuCdex1_8K1jCAlnxtB81qt3ey8SjbnoZsHlihejrsUIVsVrkLZZZXhUboqbli16gkQpyjfa9KXzKXOC3-VWSCVP/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[15] clip_image001[15]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEif9eSLA5CdUtNpZV_9tRzVs-cvsNx2XGQOLOS0RQ9OWp3tjbgcyACE1r3xNzzYwKNa_SwJufWVHY0ieqz8qW0MJfBtHJYIiSfYiUzLUI6-WMEMn8ABGZA1kUco4m4d4K-KLTqApJt50IF2/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[17] clip_image001[17]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEisAxanAAaiGJk1cAtl2X11HxFg2vsw4T11Iqvh9BNytPlPz7lcSbTRz6bRwJsixpTw6coGCaystjUPFffuujh8QBen-UZ_A0_Vih5VENZT0CHiGSyQxlYdrwOwkNSIp-8_r_B0Mwt07_HS/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[11] clip_image001[11]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgzh_mOTySG9mDPq7bltLSK8JoghrfXdYTwQIYi4nvgFWlELzs8p8VvvR8QYiB1stU3Pn8YBaAXCWtIp8XdRVWOqpUsZQW9ekyMMQcAseCAoP5driAxjxrjVXQ_zCUG73yrvnfLOLvnwrLO/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[4] clip_image001[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhznUwmb1YQ6npD6lUSZnQDt7gBzLP2E6uob6gelXk8jjVHQl2a_F2wopso8b9SBjAn8JGXNxfB65zPC_CaaPPaQFvrsTQSkKINh69iYULBJlrdcIIVcZ_xd0lqK00K2wq24drXwin5z0Kk/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhPjPh6Sn9nekUTFiAdX1jnw_AaS5eiIoVm6WlnHNyvhfeYuJBLc9fcrIBRFFR17myv4dl7zl6LT5VKKbXbIG7Yas9QMbegtV9u5YwnyDmgJdGbkiBN_yEmiBVfyGxOOzLDf3n9gX2brRKN/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[8] clip_image002[8]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhTWJg4vSDN9z0ySslcuWys7dfF2qim1HAWBb9HU1yQvFdx8AilEO3-hobId6AL0FwIUII7LbCJhNVwd_Ury4okLkB4jf_3vZDxsk9JjCf3YV-lu6lo1mIFcKiVeymbzLtyaBKzychElOc3/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[5] clip_image001[5]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyDnu6Bkl56h6G39kBxy2IiFcU_N1DoVdctKWib8OWmSPyvUR5KiBekBrKIedVgVNj7H3ULbNq3XjffiHrxH9COaB-bRIPQ52BWOtNSusjZ0Lr9NnE2HqYwV7dFVE_BQOB_a7PA2WrMnD5/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[7] clip_image001[7]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjqwKHfCwk0OBWmjxacZ5ucc_6Y9HdlMRrs3tYXv35fMdDwM3cy46-mR3Cm0lWBf7fnCacHyJyo-tG_FrHZuAe5NSAbKHGPvYzCluSVbC__cM0VXMAjnvwGmRFwszMycwidh9bLmMpsM-Ho/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[9] clip_image001[9]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj294XpH58XGxSzED_PUhNMIjzg7vfEGUYPwMtgtfNR7Cp0Ej-rVbfLUUQNfn3dPWNNl0Hm8gE78mOqhMWYpUc28VPkBK5V49Fa-ex99MGVx6SBJfqjJafPcjR1mddriGnveWTXM-HBrERe/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[11] clip_image001[11]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjz1xc4z9hLCWYQiP77A1Vlsk5GQPBOkrXuGCgN5iHnfo8Ob90PYLIlS64ahsZnIW4_lAg4jvwJfJcTmHR1DDmRSuKqCv4FCZApzZYcRVfe2Opd4DoeIaR_KtVjxf6-n4u5UjVSQnDLAK3h/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[13] clip_image001[13]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEguJlL-WtwX6ECwrDsGtKmSSwrQ14jTf2i8wI8GkYYFqnq8__sVKI6YsQ8R8C5fsYTxkI8fqs7Op99pLgA87qLwPq3nVWHEmJ9WZoRPH4jV3tY-oepvKx35ct0l3-krb9UQKxm7buWY-wgt/?imgmax=800)